This summer has seen some interesting reactions to Pope Francis’s instruction to revise the teaching on capital punishment in the Catechism of the Catholic Church so that it declares the “inadmissibility” of the death penalty in criminal justice. Much of the media treated this revision as a kind of bombshell. The Pope had changed a teaching of the Church! (So what else couldn’t a Pope change then if he really wanted to!)

Needless to say, this was media hype. The Pope hardly imposed a “new teaching”. As it stood, the teaching in the Catechism already practically closed the door to capital punishment. This current entry had been revised once before since the Catechism’s original publication in 1994 in order to make the practical prohibition stronger. Anyone who has followed debates on the death penalty over the last few decades knows how consistently the Catholic Church has been opposing it. It would be more accurate to describe Pope Francis’s revision as a logical end-point, bringing the Church’s official teaching into line with the development of its stance on a particular public policy issue.

How unwarranted, therefore, is the reaction among some of those in the “watchdog” Catholic media who have accused Pope Francis of recklessly changing “unchangeable” Church teaching, darkly hinting that the Pope’s latest action may even constitute “heresy”. What arrant nonsense from people who should know better!

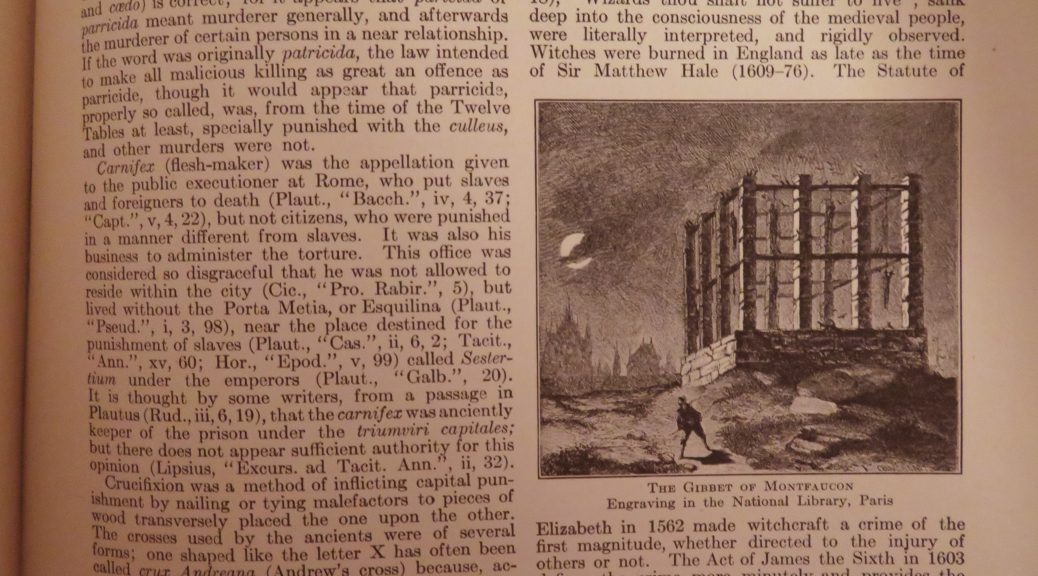

One can trace the development of the Church’s present total opposition to the use of capital punishment in criminal justice systems all the way back to the seminal work of the man who is considered the founder of the abolition movement for torture and capital punishment, Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794). Here is an example of his writing as we find it in the article on Punishment (capital) in the 1911 edition of the Catholic Encyclopedia.

“The punishment of death is not authorized by any right; for I have demonstrated that no such right exists. It is, therefore, a war of a whole nation against a citizen, whose destruction they consider as necessary or useful to the general good. But, if I can further demonstrate that it is neither necessary nor useful to the general good, I shall have gained the cause of humanity. The death of a citizen can be necessary in one case only: when, though deprived of his liberty, he has such power and connexions as may endanger the security of the nation; when his existence may produce a dangerous revolution in the established form of government. But even in this case , it can only become necessary when a nation is on the verge of recovering or losing its liberty; or in times of absolute anarchy, when the disorders themselves hold the place of laws. But in a reign of tranquility; in a form of government approved by the united wishes of the nation; in a state fortified from enemies without, and supported by strength within; …where all power is lodged in the hands of the true sovereign; where riches can purchase pleasure and not authority, there can be no necessity for taking the away the life of a subject….The punishment of death is pernicious to society, from the example of barbarity it affords. If the passions, or necessity of war, have taught men to shed the blood of their fellow creatures, the laws which are intended to moderate the ferocity of mankind should not increase it by examples of barbarity, the more horrible as this punishment is usually attended with formal pageantry Is it not absurd that the laws, which detect and punish homicide, should, in order to prevent murder, publicly commit murder themselves?” (On Crimes and Punishments, 1764)

(Pastor’s Note from the Mary Immaculate of Lourdes Parish Bulletin for August 19, 2018)